The Very Hungry Human: How consumption is destroying our wildlife biodiversity

Written by Tom Peacock

The Very Hungry Caterpillar is a popular children’s book written by Eric Carle. The book depicts a caterpillar who eats more and more each day until on the last day it turns into a butterfly. The human species consumes more and more resources each year, causing more and more damage to ecological systems. However, unlike the caterpillar, the government target of endless economic growth means there is no end in sight.

In the UK, 56% of nearly 4,000 assessed species declined in numbers between 1970 and 2013, while only 44% of species increased in numbers during the same time period [1]. Bees [2], farmland birds [3] and mammals [4] have seen particularly large declines, while livestock and deer continue to tighten their stranglehold over how the countryside is managed [5,6]. According to the UK State of Nature Report, this places the UK “among the most nature-depleted countries in the world” [1].

The state of the UK’s nature is only set to get worse as the current economic system encourages the frivolous consumption of goods, increased urbanisation through building on greenfield land, increasingly intensive farming practices and the construction of new roads and railways that carve up the landscape [7].

The way in which mainstream economics frames the environment gives justification for constantly increasing consumption. The environment is seen as a subsystem of the ever-expanding economy where environmental sources and sinks are perceived as infinite [8]. Preserved nature is just another land use that is pitted against all other land uses in the pursuit of allocative efficiency - where all resources are allocated to the uses that create the most profit [9]. Since species rich habitats are largely devoid of monetary value in their preserved state, they almost always lose out to alternative land uses which garner much higher monetary values [10].

Conservationists have attempted to even the imbalance between nature and other land uses by accepting the mainstream economic rhetoric and using it to defend nature. For example, it has become increasingly common to calculate the perceived monetary value of an ecosystem, so it can be directly compared to alternative land uses [10].

However, by accepting the mainstream economic rhetoric, conservationists are arguably accepting that increased consumption and biodiversity loss is inevitable. This then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy as developers take advantage of the strong pro-development bias in the planning system [11] to perpetually undervalue nature for economic gain [12]. This undervaluation is underpinned by the inaccuracy of assessment methodologies due to ecological uncertainties [13].

In contrast to mainstream economics, ecological economics sees the economy as a subsystem of the finite environment [8]. By framing the economy in this way, it becomes apparent that the economy can only reach a certain scale before it is causing damage to the finite environment in which it is housed. Scale refers to the quantity of resources flowing from the environment into the economy in the form of consumption and from the economy back into the environment in the form of waste [14].

Achieving sustainable scale is only possible with two conditions. Firstly, the economy can’t use more natural resources than the regenerative capacity of those resources. Secondly, the economy can’t emit more waste than the absorptive capacity of the environment [15]. If the economy is operating outside of either of these boundaries, then biodiversity loss is inevitable.

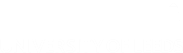

The UK is currently operating at an unsustainable scale. This is demonstrated by the planetary boundary model of sustainability which determines the biophysical limits for different environmental metrics and compares them to actual data. Using this model, the UK is breaching biophysical boundaries for ecological footprint, material footprint, CO2 emissions, phosphorous use and nitrogen use, all of which have profound impacts on wildlife biodiversity (as shown in the image below) [16].

For the UK economy to achieve sustainable scale, and therefore limit future wildlife biodiversity loss, changes need to be made to the current economic system. Politicians need to accept that economic growth, and subsequent consumption growth, isn’t a panacea and is instead an illness that is destroying the planet. Once this has been accepted, universally agreed biophysical limits must be set that the economy mustn’t breach.

As shown by the planetary boundaries model of sustainability discussed previously in this article, it is highly likely that we are already exceeding many of these biophysical limits. Therefore, policies should be put in place that encourage degrowth. Degrowth is the idea that economic growth should be slowed and there should be negative economic growth in order to bring consumption within biophysical limits [18].

Once degrowth has been achieved, a steady state economy should be targeted. A steady state economy is one that remains at a relatively consistent size, aiming to stay within the agreed upon biophysical limits [19], therefore alleviating pressure on wildlife and allowing populations to recover to sustainable levels.

If these changes aren’t made soon, there is a very real possibility that the wildlife written about in children’s stories will won’t be around for future generations to discover and enjoy.

References

- Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (2016). State of Nature 2016. Sandy. RSPB.

- Oliver, T., Isaac, N., August, T., Woodcock, B., Roy, D. and Bullock, J. (2015). Declining resilience of ecosystem functions under biodiversity loss. Nature Communications, 6(1).

- Fowlie, M. (2018). UK farmers offer hope for farmland birds. [online] RSPB. Available at: https://www.rspb.org.uk/about-the-rspb/about-us/media-centre/press-releases/hope-for-farmland-birds/ [Accessed 19 Nov. 2018].

- Carrington, D. (2018). Fifth of Britain’s wild mammals ‘at high risk of extinction’. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/jun/13/fifth-of-britains-wild-mammals-at-high-risk-of-extinction [Accessed 19 Nov. 2018].

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2017). Farming Statistics - Livestock Populations at 1 December 2017, England. London: DEFRA.

- Wäber, K., Spencer, J. and Dolman, P. (2013). Achieving landscape-scale deer management for biodiversity conservation: The need to consider sources and sinks. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 77(4), pp.726-736.

- Warwick, H. (2018). Linescapes: Remapping and Reconnecting Britain's Fragmented Wildlife. London: Vintage Publishing.

- Büscher, B., Sullivan, S., Neves, K., Igoe, J. and Brockington, D. (2012). Towards a Synthesized Critique of Neoliberal Biodiversity Conservation. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 23(2), pp.4-30.

- Investopedia. (2018). Allocational Efficiency. [online] Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/allocationalefficiency.asp [Accessed 19 Nov. 2018].

- Spash, C. (2015). Bulldozing biodiversity: The economics of offsets and trading-in Nature. Biological Conservation, 192, pp.541-551.

- Apostolopoulou, E. and Adams, W. (2017). Cutting nature to fit: Urbanization, neoliberalism and biodiversity offsetting in England. Geoforum.

- Moreno-Mateos, D., Maris, V., Béchet, A. and Curran, M. (2015). The true loss caused by biodiversity offsets. Biological Conservation, 192, pp.552-559.

- Costanza, R., d'Arge, R., de Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Limburg, K., Naeem, S., O'Neill, R., Paruelo, J., Raskin, R., Sutton, P. and van den Belt, M. (1997). The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature, 387(6630), pp.253-260.

- Daly, H. (1992). Allocation, distribution, and scale: towards an economics that is efficient, just, and sustainable. Ecological Economics, 6(3), pp.185-193.

- Daly, H. E. & Farley, J. (2005). Ecological Economics, Principles and Applications. Washington: Island Press

- O’Neill, W., Fanning, A., Lamb, W., and Steinberger, J. (2018). A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nature Sustainability. 1, pp.88-95.

- University of Leeds. (2018). Country Comparisons - A Good Life For All Within Planetary Boundaries. [online] Available at: https://goodlife.leeds.ac.uk/countries/#UnitedKingdom [Accessed 19 Nov. 2018].

- Daly, H. (2010). From a Failed-Growth Economy to a Steady-State Economy - The Solutions Journal. [online] The Solutions Journal. Available at: https://www.thesolutionsjournal.com/article/from-a-failed-growth-economy-to-a-steady-state-economy/ [Accessed 19 Nov. 2018].

- Dietz, R. and O'Neill, D. (2013). Enough is Enough: Building a Sustainable Economy in a World of Finite Resources. Abingdon: Routledge.