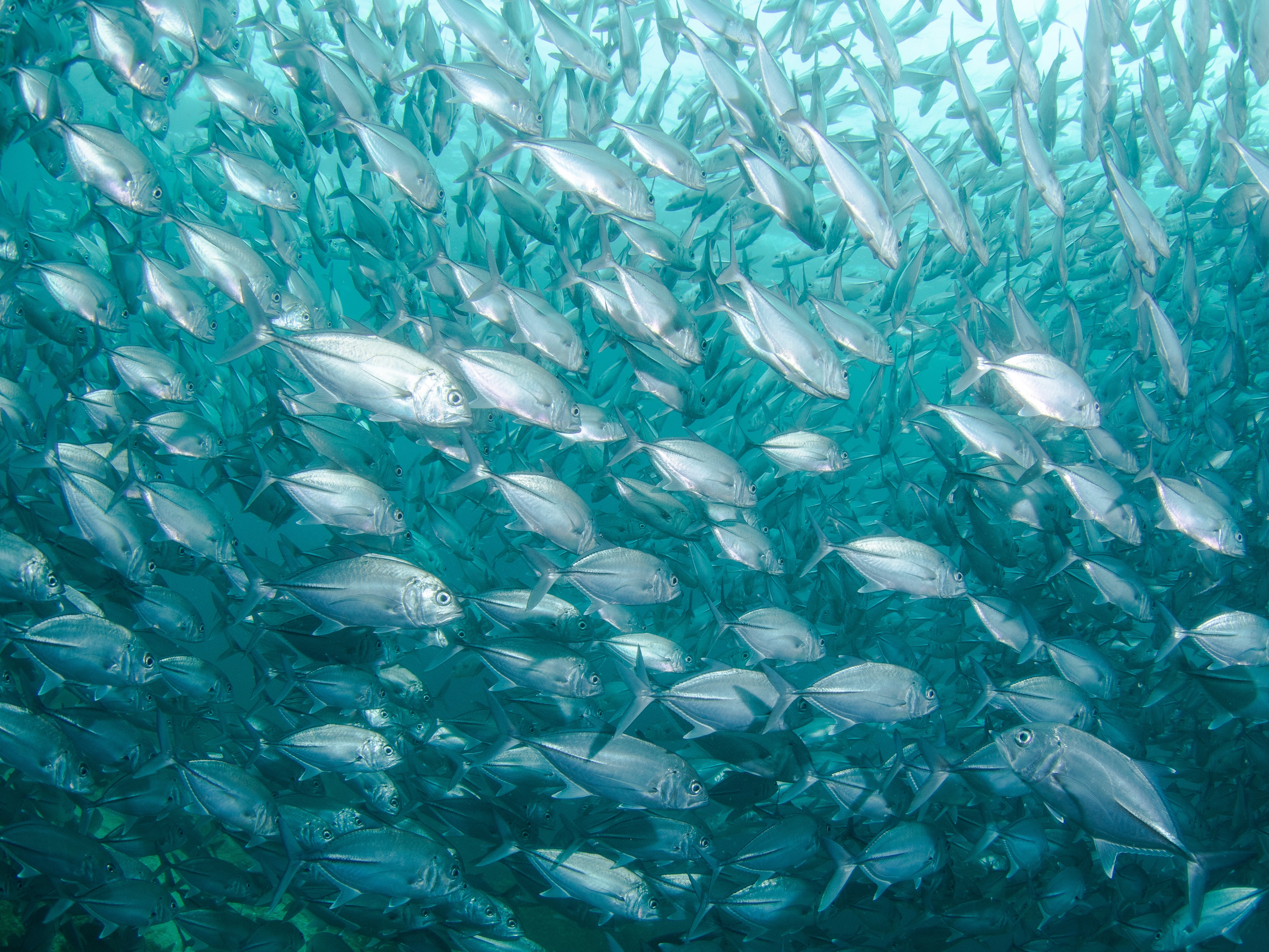

Overfishing is one of the greatest threats our oceans face. By catching more than the seas can sustain, humanity trespasses the limits of the environment and compromises the well-being of future generations. According to FAO, overexploitation of fish stocks has reached levels of 31% supported by unprecedented increases in production and global consumption . Moreover, overharvesting the oceans imposes serious constraintsto the proper development of natural ecosystems. In fact, fish stocks are dynamic and profoundly interconnected with different types of habitats, so exhaustive fishing can result in fragile ecosystems and also in a substantial decrease in the population of non-target animals .

This article will focus on unsustainable scaleas the main cause of overfishing and will provide some elements that explain the strong connection that exists between both. Scale refers to the magnitude of the economic activity in relation to the planet, which is a bigger system that supports the economy . A sustainable scale is met when the economy operates within the limits of the natural ecosystem without affecting its ability to replenish the resources employed .

The first element is the development conception that prioritisesgrowth over the preservation of the oceans. In many countries, fishery industry has been considered as a development engine . Nevertheless, the creation of new markets, technological advances and high investments in fleets not only has brought economic progress but also the inestimable destruction of ocean species . The scale created by this economic model has been far from sustainable because fishing activity has crossed the boundaries of the marine ecosystems and has reduced their capacity to recover. Likewise, fisheries production cannot be separated from the environment that sustains it, otherwise,the stability of the communities that depend on it might be disrupted as well.

Second, catching beyond the limits is also caused by an unsustainable scale due to the inherent characteristics of fish stocks. Fisheries are common-pool resources, meaning that given their size, it is not easy to prevent people from utilisingthem . In fact, since their access is usually unrestricted, the more users they have, the more resources could be overexploited . Therefore, the nature of the fisheries may give rise to an unsustainable practice. Such practice is characterisedby individuals that disregard the benefits fish stocks can supply in the long term because they can take immediate profit from the capture and transfer the real cost of overharvesting to society .

The third element that links unsustainable scale with this issue is the behaviourof fishers and can be illustrated through what is commonly called the race to fish. This situation arises when fishers need to complete certain levels of capture in a season and they rival with others to reach the amounts required. Such behaviourcreates high pressures on the seas in the short run and leads to a dramatic decline in fish populations . It also motivates individuals to purchase fishing gears that impacts the capacity of habitats to regrowth over time, reduce benefits and increment costs .

To solve this problem is necessary to establish a limit on the amount of fishes that can be taken from the ocean. This level is sustainable if the speed of the restoration process of fish stocks is not surpassed by the rate of capture . The policy instrument that meets these conditions is the Individual TransferableQuota (ITQ). ITQs are considered effective mechanisms to halt the depletion of fisheries resources and promote their regeneration . These schemes are based on a total allowed catch (TAC) that is split into quotas by the government and allocated to different actors . A TAC is a key component of this policy because it solves scale failures by defining a maximum level of capture according to the ecosystem composition. Participants can buy or sell their quotas in the market. These transactions offer fishers a right to catch that gives them adaptability to variable conditions and permits their decisions to match with conservation aims . Furthermore, evidence has proved that ITQ mechanisms stimulate efficiency, diminish costs, and have the potential to reduce fishing effort by extending seasons .

On the other hand, aspects such as unintentional catches, allocation problems,and unclear information provided by fishers should be considered in detail to apply an integrated solution . In this regard, continuous supervision and appropriate enforcement are fundamental to ensure the success of this policy . For instance, by purchasing existing quotas in markets and relocating them, regulators can make sure ecological and social objectives are accomplished .

Overall, as the elements discussed have shown, an unsustainable scale has significant repercussions on fish stocks. Policies to address this environmental issue need a holistic approach and should be designed according to the context, the local communities, and the institutions that intervene in our society . Therefore, unless we apply coordinated programs that tackle the scale and motivate the replenishment of resources, we may run out of fish in the future.

References

{2045144:CF7FJNAP};{2045144:SNW3UST7};{2045144:RBKVEIIA};{2045144:4YPEQ9RZ};{2045144:4ZI2C8LG};{2045144:PRHQQTUH};{2045144:55QMRJLT};{2045144:RG3W9M7W};{2045144:KPYPABNG};{2045144:IPS4YIZY};{2045144:IPS4YIZY};{2045144:4YPEQ9RZ};{2045144:MIUI9BE8};{2045144:HLU52BE4};{2045144:WSDANYWT};{2045144:3Y4PWYYT};{2045144:4ZI2C8LG};{2045144:BTV7VY8G};{2045144:HLU52BE4};{2045144:IPS4YIZY};{2045144:55QMRJLT}

default

asc

no

306

%7B%22status%22%3A%22success%22%2C%22updateneeded%22%3Afalse%2C%22instance%22%3A%22zotpress-a9ab94e8eb7c97658d602db6986f9422%22%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22request_last%22%3A0%2C%22request_next%22%3A0%2C%22used_cache%22%3Atrue%7D%2C%22data%22%3A%5B%7B%22key%22%3A%22RG3W9M7W%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Young%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222001%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EYoung%20E.%20State%20Intervention%20and%20Abuse%20of%20the%20Commons%3A%20Fisheries%20Development%20in%20Baja%20California%20Sur%2C%20Mexico.%20Annals%20of%20the%20Association%20of%20American%20Geographers%20%5BInternet%5D.%202001%20%5Bcited%202018%20May%2031%5D%3B91%282%29%3A283%26%23x2013%3B306.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fonlinelibrary.wiley.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Fabs%5C%2F10.1111%5C%2F0004-5608.00244%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fonlinelibrary.wiley.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Fabs%5C%2F10.1111%5C%2F0004-5608.00244%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22State%20Intervention%20and%20Abuse%20of%20the%20Commons%3A%20Fisheries%20Development%20in%20Baja%20California%20Sur%2C%20Mexico%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Emily%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Young%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22In%20many%20countries%20worldwide%2C%20the%20logic%20of%20the%20tragedy%20of%20the%20commons%20model%20underlies%20policies%20concerning%20the%20development%20and%20conservation%20of%20natural%20resources.%20In%20this%20paper%2C%20I%20use%20the%20case%20of%20fisheries%20in%20Baja%20California%20Sur%2C%20Mexico%20to%20critique%20the%20tragedy%20of%20the%20commons%20model%20as%20a%20metaphor%20for%20understanding%20increasingly%20abusive%20patterns%20of%20marine%20resource%20use.%20I%20show%20how%20past%20fishery%20policies%20have%20fomented%20a%20tragedy%20of%20incursion%20in%20two%20key%20fishing%20grounds%20in%20Baja%20California%20Sur%2C%20Laguna%20San%20Ignacio%20and%20Bah%5Cu00eda%20Magdalena%2C%20by%20encouraging%20outside%20encroachment%20and%20increasingly%20widespread%20resource%20poaching.%20Although%20contemporary%20efforts%20to%20encourage%20greater%20private%20sector%20involvement%20in%20fishery%20development%20have%20exacerbated%20problems%20of%20outside%20encroachment%2C%20they%20have%20also%20opened%20up%20new%20opportunities%20for%20inshore%20fishing%20communities%20to%20reassert%20control%20over%20local%20resources%20and%20promote%20marine%20stewardship.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222001%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1111%5C%2F0004-5608.00244%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%221467-8306%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fonlinelibrary.wiley.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Fabs%5C%2F10.1111%5C%2F0004-5608.00244%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T12%3A24%3A56Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22CF7FJNAP%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22FAO%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222016%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EFAO.%20Contributing%20to%20food%20security%20and%20nutrition%20for%20all.%20Rome%3B%202016.%20%28The%20state%20of%20world%20fisheries%20and%20aquaculture%29.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Contributing%20to%20food%20security%20and%20nutrition%20for%20all%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22FAO%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222016%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-92-5-109185-2%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T12%3A21%3A51Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22SNW3UST7%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Hilborn%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222015-09%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EHilborn%20R%2C%20Fulton%20EA%2C%20Green%20BS%2C%20Hartmann%20K%2C%20Tracey%20SR%2C%20Watson%20RA.%20When%20is%20a%20fishery%20sustainable%3F%20Canadian%20Journal%20of%20Fisheries%20and%20Aquatic%20Sciences%20%5BInternet%5D.%202015%20Sep%20%5Bcited%202018%20May%2031%5D%3B72%289%29%3A1433%26%23x2013%3B1441.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.nrcresearchpress.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2F10.1139%5C%2Fcjfas-2015-0062%27%3Ehttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.nrcresearchpress.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2F10.1139%5C%2Fcjfas-2015-0062%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22When%20is%20a%20fishery%20sustainable%3F%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ray%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hilborn%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Elizabeth%20A.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Fulton%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Bridget%20S.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Green%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Klaas%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hartmann%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Sean%20R.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Tracey%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Reg%20A.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Watson%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Despite%20the%20many%20scienti%5Cufb01c%20and%20public%20discussions%20on%20the%20sustainability%20of%20%5Cufb01sheries%2C%20there%20are%20still%20great%20differences%20in%20both%20perception%20and%20de%5Cufb01nition%20of%20the%20concept.%20Most%20authors%20now%20suggest%20that%20sustainability%20is%20best%20de%5Cufb01ned%20as%20the%20ability%20to%20sustain%20goods%20and%20services%20to%20human%20society%2C%20with%20social%20and%20economic%20factors%20to%20be%20considered%20along%20with%20environmental%20impacts.%20The%20result%20has%20been%20that%20each%20group%20%28scientists%2C%20economists%2C%20non-governmental%20organizations%20%28NGOs%29%2C%20etc.%29%20de%5Cufb01nes%20%5Cu201csustainable%20seafood%5Cu201d%20using%20whatever%20criteria%20it%20considers%20most%20important%2C%20and%20the%20same%20%5Cufb01sh%20product%20may%20be%20deemed%20sustainable%20by%20one%20group%20and%20totally%20unsustainable%20by%20another%20one.%20We%20contend%2C%20however%2C%20that%20there%20is%20now%20extensive%20evidence%20that%20an%20ecological%20focus%20alone%20does%20not%20guarantee%20long-term%20sustainability%20of%20any%20form%20and%20that%20seafood%20sustainability%20must%20consistently%20take%20on%20a%20socio-ecological%20perspective%20if%20it%20is%20to%20be%20effective%20across%20cultures%20and%20in%20the%20future.%20The%20sustainability%20of%20seafood%20production%20depends%20not%20on%20the%20abundance%20of%20a%20%5Cufb01sh%20stock%2C%20but%20on%20the%20ability%20of%20the%20%5Cufb01shery%20management%20system%20to%20adjust%20%5Cufb01shing%20pressure%20to%20appropriate%20levels.%20While%20there%20are%20scienti%5Cufb01c%20standards%20to%20judge%20the%20sustainability%20of%20food%20production%2C%20once%20we%20examine%20ecological%2C%20social%2C%20and%20economic%20aspects%20of%20sustainability%2C%20there%20is%20no%20unique%20scienti%5Cufb01c%20standard.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22September%202015%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1139%5C%2Fcjfas-2015-0062%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220706-652X%2C%201205-7533%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.nrcresearchpress.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2F10.1139%5C%2Fcjfas-2015-0062%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T08%3A06%3A52Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22PRHQQTUH%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Coulthard%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222011-05%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ECoulthard%20S%2C%20Johnson%20D%2C%20McGregor%20JA.%20Poverty%2C%20sustainability%20and%20human%20wellbeing%3A%20A%20social%20wellbeing%20approach%20to%20the%20global%20fisheries%20crisis.%20Global%20Environmental%20Change%20%5BInternet%5D.%202011%20May%20%5Bcited%202018%20May%2031%5D%3B21%282%29%3A453%26%23x2013%3B463.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.sciencedirect.com%5C%2Fscience%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fpii%5C%2FS0959378011000045%27%3Ehttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.sciencedirect.com%5C%2Fscience%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fpii%5C%2FS0959378011000045%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Poverty%2C%20sustainability%20and%20human%20wellbeing%3A%20A%20social%20wellbeing%20approach%20to%20the%20global%20fisheries%20crisis%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Sarah%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Coulthard%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Derek%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Johnson%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22J.%20Allister%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22McGregor%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20purpose%20of%20this%20paper%20is%20to%20explore%20the%20extent%20to%20which%20a%20social%20wellbeing%20approach%20can%20offer%20a%20useful%20way%20of%20addressing%20the%20policy%20challenge%20of%20reconciling%20poverty%20and%20environmental%20objectives%20for%20development%20policy%20makers.%20In%20order%20to%20provide%20detail%20from%20engagement%20with%20a%20specific%20policy%20challenge%20it%20takes%20as%20its%20illustrative%20example%20the%20global%20fisheries%20crisis.%20This%20crisis%20portends%20not%20only%20an%20environmental%20disaster%20but%20also%20a%20catastrophe%20for%20human%20development%20and%20for%20the%20millions%20of%20people%20directly%20dependent%20upon%20fish%20resources%20for%20their%20livelihoods%20and%20food%20security.%20The%20paper%20presents%20the%20argument%20for%20framing%20the%20policy%20problem%20using%20a%20social%20conception%20of%20human%20wellbeing%2C%20suggesting%20that%20this%20approach%20provides%20insights%20which%20have%20the%20potential%20to%20improve%20fisheries%20policy%20and%20governance.%20By%20broadening%20the%20scope%20of%20analysis%20to%20consider%20values%2C%20aspirations%20and%20motivations%20and%20by%20focusing%20on%20the%20wide%20range%20of%20social%20relationships%20that%20are%20integral%20to%20people%20achieving%20their%20wellbeing%2C%20it%20provides%20a%20basis%20for%20better%20understanding%20the%20competing%20interests%20in%20fisheries%20which%20generate%20conflict%20and%20which%20often%20undermine%20existing%20policy%20regimes.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22May%202011%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1016%5C%2Fj.gloenvcha.2011.01.003%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220959-3780%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.sciencedirect.com%5C%2Fscience%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fpii%5C%2FS0959378011000045%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T08%3A06%3A41Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22BTV7VY8G%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Parslow%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222010-11%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EParslow%20J.%20Individual%20transferable%20quotas%20and%20the%20%26%23x201C%3Btragedy%20of%20the%20commons.%26%23x201D%3B%20Canadian%20Journal%20of%20Fisheries%20and%20Aquatic%20Sciences%20%5BInternet%5D.%202010%20Nov%20%5Bcited%202018%20May%2031%5D%3B67%2811%29%3A1889%26%23x2013%3B1896.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.nrcresearchpress.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Fabs%5C%2F10.1139%5C%2FF10-104%27%3Ehttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.nrcresearchpress.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Fabs%5C%2F10.1139%5C%2FF10-104%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Individual%20transferable%20quotas%20and%20the%20%5Cu201ctragedy%20of%20the%20commons%5Cu201d%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22John%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Parslow%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20allocation%20of%20individual%20transferable%20quotas%20%28ITQs%29%20as%20shares%20of%20a%20total%20allowable%20catch%20%28TAC%29%20is%20now%20widely%20practised%20in%20fisheries%20management%2C%20but%20is%20not%20without%20controversy.%20It%20is%20often%20suggested%20that%20the%20possession%20of%20ITQs%20should%20provide%20an%20incentive%20for%20fishers%20to%20exercise%20stewardship%20of%20the%20resource.%20Quota%20holders%20acting%20in%20their%20economic%20self-interest%20should%20collectively%20exercise%20stewardship%2C%20setting%20TACs%20and%20supporting%20enforcement%20measures%20to%20maximize%20the%20present%20value%20of%20future%20profit%20streams.%20But%20it%20is%20in%20the%20economic%20self-interest%20of%20an%20individual%20fisher%20possessing%20ITQ%20to%20take%20additional%20unreported%20catch%2C%20through%20discarding%2C%20high-grading%2C%20or%20quota-busting.%20Thus%2C%20ITQs%20in%20themselves%20will%20not%20prevent%20a%20%5Cu201ctragedy%20of%20the%20commons%5Cu201d%2C%20unless%20there%20is%20sufficient%20compliance%20monitoring%20and%20enforcement%20to%20deter%20hidden%20catches.%20ITQs%2C%20with%20adequate%20enforcement%2C%20have%20been%20demonstrated%20to%20effectively%20address%20the%20race%20to%20fish%20and%20result%20in%20improved%20sustainability%20and%20profitability.%20There%20are%20questions%20of%20equit...%2C%20L%27allocation%20de%20quotas%20individuels%20transf%5Cu00e9rables%20%28QIT%29%20comme%20parts%20du%20total%20autoris%5Cu00e9%20des%20captures%20%28TAC%29%20est%20commun%5Cu00e9ment%20utilis%5Cu00e9e%20dans%20la%20gestion%20des%20p%5Cu00eaches%2C%20mais%20elle%20n%27est%20pas%20sans%20soulever%20des%20controverses.%20On%20indique%20souvent%20que%20la%20possession%20d%27un%20QIT%20devrait%20inciter%20les%20p%5Cu00eacheurs%20%5Cu00e0%20exercer%20une%20responsabilit%5Cu00e9%20de%20g%5Cu00e9rance%20de%20la%20ressource.%20Les%20possesseurs%20de%20quotas%20agissant%20pour%20leurs%20int%5Cu00e9r%5Cu00eat%20personnel%20devraient%20exercer%20collectivement%20la%20g%5Cu00e9rance%2C%20en%20d%5Cu00e9terminant%20les%20TAC%20et%20en%20appuyant%20les%20mesures%20d%27application%20des%20r%5Cu00e8glements%20afin%20de%20maximiser%20la%20valeur%20actuelle%20des%20perspectives%20futures%20de%20profit.%20Mais%20c%27est%20dans%20l%27int%5Cu00e9r%5Cu00eat%20%5Cu00e9conomique%20personnel%20du%20p%5Cu00eacheur%20individuel%20qui%20poss%5Cu00e8de%20un%20QIT%20de%20faire%20des%20r%5Cu00e9coltes%20additionnelles%20non%20signal%5Cu00e9es%2C%20en%20faisant%20des%20rejets%2C%20en%20%5Cu00e9cr%5Cu00e9mant%20les%20captures%20ou%20en%20d%5Cu00e9passant%20les%20quotas.%20Ainsi%2C%20les%20QIT%20en%20eux-m%5Cu00eames%20n%27emp%5Cu00eachent%20pas%20l%27arriv%5Cu00e9e%20d%27une%20%5Cu00ab%20trag%5Cu00e9die%20des%20richesses%20communes%20%5Cu00bb%20%5Cu00e0%20moins%20qu%27il%20n%27y%20ait%20suffisamment%20de%20surveillance%20du%20respect%20des%20r%5Cu00e8glements%20et%20de%20leur%20application%20pour%20d...%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22November%202010%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1139%5C%2FF10-104%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220706-652X%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.nrcresearchpress.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Fabs%5C%2F10.1139%5C%2FF10-104%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T08%3A06%3A31Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22RBKVEIIA%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Daly%20and%20Farley%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222011-01%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EDaly%20HE%2C%20Farley%20J.%20Ecological%20Economics%2C%20Second%20Edition%3A%20Principles%20and%20Applications.%20Island%20Press%3B%202011.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Ecological%20Economics%2C%20Second%20Edition%3A%20Principles%20and%20Applications%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Herman%20E.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Daly%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Joshua%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Farley%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22In%20its%20first%20edition%2C%20this%20book%20helped%20to%20define%20the%20emerging%20field%20of%20ecological%20economics.%20This%20new%20edition%20surveys%20the%20field%20today.%20It%20incorporates%20all%20of%20the%20latest%20research%20findings%20and%20grounds%20economic%20inquiry%20in%20a%20more%20robust%20understanding%20of%20human%20needs%20and%20behavior.%20Humans%20and%20ecological%20systems%2C%20it%20argues%2C%20are%20inextricably%20bound%20together%20in%20complex%20and%20long-misunderstood%20ways.%20According%20to%20ecological%20economists%2C%20conventional%20economics%20does%20not%20reflect%20adequately%20the%20value%20of%20essential%20factors%20like%20clean%20air%20and%20water%2C%20species%20diversity%2C%20and%20social%20and%20generational%20equity.%20By%20excluding%20biophysical%20and%20social%20systems%20from%20their%20analyses%2C%20many%20conventional%20economists%20have%20overlooked%20problems%20of%20the%20increasing%20scale%20of%20human%20impacts%20and%20the%20inequitable%20distribution%20of%20resources.%20This%20introductory-level%20textbook%20is%20designed%20specifically%20to%20address%20this%20significant%20flaw%20in%20economic%20thought.%20The%20book%20describes%20a%20relatively%20new%20%5Cu201ctransdiscipline%5Cu201d%20that%20incorporates%20insights%20from%20the%20biological%2C%20physical%2C%20and%20social%20sciences.%20It%20provides%20students%20with%20a%20foundation%20in%20traditional%20neoclassical%20economic%20thought%2C%20but%20places%20that%20foundation%20within%20an%20interdisciplinary%20framework%20that%20embraces%20the%20linkages%20among%20economic%20growth%2C%20environmental%20degradation%2C%20and%20social%20inequity.%20In%20doing%20so%2C%20it%20presents%20a%20revolutionary%20way%20of%20viewing%20the%20world.%20The%20second%20edition%20of%20Ecological%20Economics%20provides%20a%20clear%2C%20readable%2C%20and%20easy-to-understand%20overview%20of%20a%20field%20of%20study%20that%20continues%20to%20grow%20in%20importance.%20It%20remains%20the%20only%20stand-alone%20textbook%20that%20offers%20a%20complete%20explanation%20of%20theory%20and%20practice%20in%20the%20discipline.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22January%202011%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-1-59726-991-9%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T08%3A06%3A15Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%223Y4PWYYT%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Birkenbach%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222017-04%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EBirkenbach%20AM%2C%20Kaczan%20DJ%2C%20Smith%20MD.%20Catch%20shares%20slow%20the%20race%20to%20fish.%20Nature%20%5BInternet%5D.%202017%20Apr%20%5Bcited%202018%20May%2031%5D%3B544%287649%29%3A223%26%23x2013%3B226.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.nature.com%5C%2Farticles%5C%2Fnature21728%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.nature.com%5C%2Farticles%5C%2Fnature21728%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Catch%20shares%20slow%20the%20race%20to%20fish%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Anna%20M.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Birkenbach%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22David%20J.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Kaczan%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Martin%20D.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Smith%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22In%20fisheries%2C%20the%20tragedy%20of%20the%20commons%20manifests%20as%20a%20competitive%20race%20to%20fish%20that%20compresses%20fishing%20seasons%2C%20resulting%20in%20ecological%20damage%2C%20economic%20waste%2C%20and%20occupational%20hazards1%2C2%2C3%2C4%2C5%2C6%2C7%2C8.%20Catch%20shares%20are%20hypothesized%20to%20halt%20the%20race%20by%20securing%20each%20individual%5Cu2019s%20right%20to%20a%20portion%20of%20the%20total%20catch%2C%20but%20there%20is%20evidence%20for%20this%20from%20selected%20examples%20only2%2C9.%20Here%20we%20systematically%20analyse%20natural%20experiments%20to%20test%20whether%20catch%20shares%20reduce%20racing%20in%2039%20US%20fisheries.%20We%20compare%20each%20fishery%20treated%20with%20catch%20shares%20to%20an%20individually%20matched%20control%20before%20and%20after%20the%20policy%20change.%20We%20estimate%20an%20average%20policy%20treatment%20effect%20in%20a%20pooled%20model%20and%20in%20a%20meta-analysis%20that%20combines%20separate%20estimates%20for%20each%20treatment%5Cu2013control%20pair.%20Consistent%20with%20the%20theory%20that%20market-based%20management%20ends%20the%20race%20to%20fish%2C%20we%20find%20strong%20evidence%20that%20catch%20shares%20extend%20fishing%20seasons.%20This%20evidence%20informs%20the%20current%20debate%20over%20expanding%20the%20use%20of%20market-based%20regulation%20to%20other%20fisheries.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22April%202017%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1038%5C%2Fnature21728%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%221476-4687%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.nature.com%5C%2Farticles%5C%2Fnature21728%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T08%3A06%3A09Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%224YPEQ9RZ%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Costanza%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222014-12%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ECostanza%20R%2C%20Cumberland%20JH%2C%20Daly%20H%2C%20Goodland%20R%2C%20Norgaard%20RB%2C%20Kubiszewski%20I%2C%20et%20al.%20An%20Introduction%20to%20Ecological%20Economics%2C%20Second%20Edition.%20CRC%20Press%3B%202014.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22An%20Introduction%20to%20Ecological%20Economics%2C%20Second%20Edition%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robert%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Costanza%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22John%20H.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Cumberland%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Herman%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Daly%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robert%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Goodland%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Richard%20B.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Norgaard%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ida%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Kubiszewski%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Carol%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Franco%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22From%20Empty-World%20Economics%20to%20Full-World%20Economics%20Ecological%20economics%20explores%20new%20ways%20of%20thinking%20about%20how%20we%20manage%20our%20lives%20and%20our%20planet%20to%20achieve%20a%20sustainable%2C%20equitable%2C%20and%20prosperous%20future.%20Ecological%20economics%20extends%20and%20integrates%20the%20study%20and%20management%20of%20both%20%5C%22nature%27s%20household%5C%22%20and%20%5C%22humankind%27s%20household%5C%22%5Cu2014An%20Introduction%20to%20Ecological%20Economics%2C%20Second%20Edition%2C%20the%20first%20update%20and%20expansion%20of%20this%20classic%20text%20in%2015%20years%2C%20describes%20new%20approaches%20to%20achieving%20a%20sustainable%20and%20desirable%20human%20presence%20on%20Earth.%20Written%20by%20the%20top%20experts%20in%20the%20field%2C%20it%20addresses%20the%20necessity%20for%20an%20innovative%20approach%20to%20integrated%20environmental%2C%20social%2C%20and%20economic%20analysis%20and%20management%2C%20and%20describes%20policies%20aimed%20at%20achieving%20our%20shared%20goals.%20Demands%20a%20Departure%20from%20Business%20as%20Usual%20The%20book%20begins%20with%20a%20description%20of%20prevailing%20interdependent%20environmental%2C%20economic%2C%20and%20social%20issues%20and%20their%20underlying%20causes%2C%20and%20offers%20guidance%20on%20designing%20policies%20and%20instruments%20capable%20of%20adequately%20coping%20with%20these%20problems.%20It%20documents%20the%20historical%20development%20of%20the%20disciplines%20of%20economics%20and%20ecology%2C%20and%20explores%20how%20they%20have%20evolved%20so%20differently%20from%20a%20shared%20conceptual%20base.%20Structured%20into%20four%20sections%2C%20it%20also%20presents%20various%20ideas%20and%20models%20in%20their%20proper%20chronological%20context%2C%20details%20the%20fundamental%20principles%20of%20ecological%20economics%2C%20and%20outlines%20prospects%20for%20the%20future.%20What%5Cu2019s%20New%20in%20the%20Second%20Edition%3A%20Includes%20several%20new%20pieces%20and%20updates%20in%20each%20section%20Adds%20a%20series%20of%20independently%20authored%20%5C%22boxes%5C%22%20to%20expand%20and%20update%20information%20in%20the%20current%20text%20Addresses%20the%20historical%20development%20of%20economics%20and%20ecology%20and%20the%20recent%20progress%20in%20integrating%20the%20study%20of%20humans%20and%20the%20rest%20of%20nature%20Covers%20the%20basic%20concepts%20and%20applications%20of%20ecological%20economics%20in%20language%20accessible%20to%20a%20broad%20audience%20An%20Introduction%20to%20Ecological%20Economics%2C%20Second%20Edition%20can%20be%20used%20in%20an%20introductory%20undergraduate%20or%20graduate%20course%3B%20requires%20no%20prior%20knowledge%20of%20mathematics%2C%20economics%2C%20or%20ecology%3B%20provides%20a%20unified%20understanding%20of%20natural%20and%20human-dominated%20ecosystems%3B%20and%20reintegrates%20the%20market%20economy%20within%20society%20and%20the%20rest%20of%20nature.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22December%202014%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-1-56670-684-1%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T08%3A05%3A56Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%2255QMRJLT%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Ostrom%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222008-07%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EOstrom%20E.%20The%20Challenge%20of%20Common-Pool%20Resources.%20Environment%3A%20Science%20and%20Policy%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20%5BInternet%5D.%202008%20Jul%20%5Bcited%202018%20May%2031%5D%3B50%284%29%3A8%26%23x2013%3B21.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.3200%5C%2FENVT.50.4.8-21%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.3200%5C%2FENVT.50.4.8-21%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20Challenge%20of%20Common-Pool%20Resources%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Elinor%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Ostrom%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22July%202008%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.3200%5C%2FENVT.50.4.8-21%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220013-9157%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.3200%5C%2FENVT.50.4.8-21%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T08%3A05%3A04Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22HLU52BE4%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Soliman%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222014-03%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ESoliman%20A.%20Using%20individual%20transferable%20quotas%20%28ITQs%29%20to%20achieve%20social%20policy%20objectives%3A%20A%20proposed%20intervention.%20Marine%20Policy%20%5BInternet%5D.%202014%20Mar%20%5Bcited%202018%20May%2031%5D%3B45%3A76%26%23x2013%3B81.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.sciencedirect.com%5C%2Fscience%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fpii%5C%2FS0308597X13002807%27%3Ehttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.sciencedirect.com%5C%2Fscience%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fpii%5C%2FS0308597X13002807%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Using%20individual%20transferable%20quotas%20%28ITQs%29%20to%20achieve%20social%20policy%20objectives%3A%20A%20proposed%20intervention%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Adam%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Soliman%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22ITQs%20offer%20environmental%20and%20economic%20benefits%2C%20including%20better%20conservation%20of%20a%20fish%20stock%20and%20greater%20profitability%20for%20fishers.%20With%20some%20limitations%2C%20they%20achieve%20fairly%20good%20alignment%20between%20the%20profit%20incentive%20and%20stewardship%20objectives.%20Nevertheless%2C%20critics%20have%20objected%20to%20ITQ%20schemes%20because%20of%20such%20factors%20as%20the%20%5Cu201carmchair%20fishing%5Cu201d%20phenomenon%2C%20unfairness%20to%20the%20public%20%28the%20owner%20of%20the%20fish%29%2C%20economic%20and%20social%20damage%20to%20remote%20communities%2C%20and%20increased%20concentration%20within%20the%20fishery.%20Economists%20generally%20dismiss%20these%20as%20distributional%20issues%20rather%20than%20matters%20of%20efficiency%20or%20economics%2C%20but%20economic%20principles%20are%20clearly%20not%20the%20only%20factors%20that%20may%20require%20attention%20or%20action%20from%20a%20government%20or%20regulator.%20This%20paper%20proposes%20an%20intervention%20that%20addresses%20these%20concerns%20within%20the%20context%20of%20an%20ITQ%20scheme.%20The%20intervention%20does%20not%20reduce%20the%20permanence%20or%20values%20of%20ITQs%2C%20and%20therefore%20retains%20the%20benefits%20that%20ITQs%20are%20designed%20to%20deliver.%20Nevertheless%2C%20the%20intervention%20addresses%20the%20criticisms%20identified%20above.%20Modifications%20of%20the%20intervention%20may%20enable%20additional%20goals%20and%20benefits%20to%20be%20achieved%20as%20well.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22March%202014%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1016%5C%2Fj.marpol.2013.11.021%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220308-597X%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.sciencedirect.com%5C%2Fscience%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fpii%5C%2FS0308597X13002807%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T08%3A04%3A30Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22MIUI9BE8%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Costello%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222008-09%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ECostello%20C%2C%20Gaines%20SD%2C%20Lynham%20J.%20Can%20Catch%20Shares%20Prevent%20Fisheries%20Collapse%3F%20Science%20%5BInternet%5D.%202008%20Sep%20%5Bcited%202018%20May%2031%5D%3B321%285896%29%3A1678%26%23x2013%3B1681.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fscience.sciencemag.org%5C%2Fcontent%5C%2F321%5C%2F5896%5C%2F1678%27%3Ehttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fscience.sciencemag.org%5C%2Fcontent%5C%2F321%5C%2F5896%5C%2F1678%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Can%20Catch%20Shares%20Prevent%20Fisheries%20Collapse%3F%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Christopher%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Costello%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Steven%20D.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Gaines%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22John%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Lynham%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Recent%20reports%20suggest%20that%20most%20of%20the%20world%27s%20commercial%20fisheries%20could%20collapse%20within%20decades.%20Although%20poor%20fisheries%20governance%20is%20often%20implicated%2C%20evaluation%20of%20solutions%20remains%20rare.%20Bioeconomic%20theory%20and%20case%20studies%20suggest%20that%20rights-based%20catch%20shares%20can%20provide%20individual%20incentives%20for%20sustainable%20harvest%20that%20is%20less%20prone%20to%20collapse.%20To%20test%20whether%20catch-share%20fishery%20reforms%20achieve%20these%20hypothetical%20benefits%2C%20we%20have%20compiled%20a%20global%20database%20of%20fisheries%20institutions%20and%20catch%20statistics%20in%2011%2C135%20fisheries%20from%201950%20to%202003.%20Implementation%20of%20catch%20shares%20halts%2C%20and%20even%20reverses%2C%20the%20global%20trend%20toward%20widespread%20collapse.%20Institutional%20change%20has%20the%20potential%20for%20greatly%20altering%20the%20future%20of%20global%20fisheries.%20Global%20catch%20statistics%20since%201950%20suggest%20that%20fisheries%20will%20be%20half%20as%20likely%20to%20collapse%20if%20fisherman%20have%20a%20sustainability%20incentive%20through%20a%20guaranteed%20right%20of%20harvest.%20Global%20catch%20statistics%20since%201950%20suggest%20that%20fisheries%20will%20be%20half%20as%20likely%20to%20collapse%20if%20fisherman%20have%20a%20sustainability%20incentive%20through%20a%20guaranteed%20right%20of%20harvest.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22September%202008%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1126%5C%2Fscience.1159478%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220036-8075%2C%201095-9203%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fscience.sciencemag.org%5C%2Fcontent%5C%2F321%5C%2F5896%5C%2F1678%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T08%3A04%3A29Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22WSDANYWT%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Grafton%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222006-03%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EGrafton%20RQ%2C%20Arnason%20R%2C%20Bj%26%23xF8%3Brndal%20T%2C%20Campbell%20D%2C%20Campbell%20HF%2C%20Clark%20CW%2C%20et%20al.%20Incentive-based%20approaches%20to%20sustainable%20fisheries.%20Canadian%20Journal%20of%20Fisheries%20and%20Aquatic%20Sciences%20%5BInternet%5D.%202006%20Mar%20%5Bcited%202018%20May%2031%5D%3B63%283%29%3A699%26%23x2013%3B710.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.nrcresearchpress.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Fabs%5C%2F10.1139%5C%2Ff05-247%27%3Ehttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.nrcresearchpress.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Fabs%5C%2F10.1139%5C%2Ff05-247%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Incentive-based%20approaches%20to%20sustainable%20fisheries%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22R%20Quentin%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Grafton%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ragnar%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Arnason%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Trond%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Bj%5Cu00f8rndal%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22David%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Campbell%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Harry%20F%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Campbell%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Colin%20W%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Clark%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robin%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Connor%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Diane%20P%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Dupont%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22R%5Cu00f6gnvaldur%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hannesson%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ray%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hilborn%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22James%20E%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Kirkley%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Tom%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Kompas%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Daniel%20E%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Lane%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Gordon%20R%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Munro%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Sean%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Pascoe%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Dale%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Squires%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Stein%20Ivar%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Steinshamn%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Bruce%20R%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Turris%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Quinn%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Weninger%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20failures%20of%20traditional%20target-species%20management%20have%20led%20many%20to%20propose%20an%20ecosystem%20approach%20to%20fisheries%20to%20promote%20sustainability.%20The%20ecosystem%20approach%20is%20necessary%2C%20especially%20to%20account%20for%20fishery%5Cu0096ecosystem%20interactions%2C%20but%20by%20itself%20is%20not%20sufficient%20to%20address%20two%20important%20factors%20contributing%20to%20unsustainable%20fisheries%3A%20inappropriate%20incentives%20bearing%20on%20fishers%20and%20the%20ineffective%20governance%20that%20frequently%20exists%20in%20commercial%2C%20developed%20fisheries%20managed%20primarily%20by%20total-harvest%20limits%20and%20input%20controls.%20We%20contend%20that%20much%20greater%20emphasis%20must%20be%20placed%20on%20fisher%20motivation%20when%20managing%20fisheries.%20Using%20evidence%20from%20more%20than%20a%20dozen%20natural%20experiments%20in%20commercial%20fisheries%2C%20we%20argue%20that%20incentive-based%20approaches%20that%20better%20specify%20community%20and%20individual%20harvest%20or%20territorial%20rights%20and%20price%20ecosystem%20services%20and%20that%20are%20coupled%20with%20public%20research%2C%20monitoring%2C%20and%20effective%20oversight%20promote%20sustainable%20fisheries.%2C%20Les%20%5Cu00e9checs%20des%20am%5Cu00e9nagements%20traditionnels%20centr%5Cu00e9s%20sur%20les%20esp%5Cu00e8ces-cibles%20ont%20incit%5Cu00e9%20plusieurs%20chercheurs%20%5Cu00e0%20proposer%20des%20approches%20halieutiques%20bas%5Cu00e9es%20sur%20les%20%5Cu00e9cosyst%5Cu00e8mes%20pour%20favoriser%20les%20p%5Cu00eaches%20durables.%20L%27approche%20%5Cu00e9cosyst%5Cu00e9mique%20est%20n%5Cu00e9cessaire%2C%20en%20particulier%2C%20pour%20tenir%20compte%20des%20interactions%20p%5Cu00eache%5Cu0096%5Cu00e9cosyst%5Cu00e8me%3B%20elle%20ne%20suffit%20pas%2C%20cependant%2C%20par%20elle-m%5Cu00eame%20pour%20r%5Cu00e9gler%20deux%20facteurs%20importants%20qui%20contribuent%20%5Cu00e0%20rendre%20les%20p%5Cu00eaches%20non%20durables%20%3A%20les%20incitations%20insuffisantes%20pour%20les%20p%5Cu00eacheurs%20et%20la%20gestion%20inefficace%20souvent%20pr%5Cu00e9sente%20dans%20les%20p%5Cu00eaches%20commerciales%20d%5Cu00e9velopp%5Cu00e9es%20qui%20sont%20r%5Cu00e9gies%20principalement%20par%20des%20limites%20%5Cu00e0%20la%20r%5Cu00e9colte%20totale%20et%20par%20des%20contr%5Cu00f4les%20d%27entr%5Cu00e9e.%20Nous%20croyons%20qu%27on%20doit%20mettre%20beaucoup%20plus%20l%27accent%20sur%20la%20motivation%20des%20p%5Cu00eacheurs%20dans%20la%20gestion%20de%20la%20p%5Cu00eache.%20En%20utilisant%20des%20donn%5Cu00e9es%20provenant%20de%20plus%20d%27une%20douzaine%20d%27exp%5Cu00e9riences%20naturelles%20de%20p%5Cu00eache%20commerciale%2C%20nous%20cherchons%20%5Cu00e0%20d%5Cu00e9montrer%20que%20des%20approches%20fond%5Cu00e9es%20sur%20les%20incitations%20qui%20pr%5Cu00e9cisent%20mieux%20la%20communaut%5Cu00e9%2C%20les%20r%5Cu00e9coltes%20in...%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22March%202006%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1139%5C%2Ff05-247%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220706-652X%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.nrcresearchpress.com%5C%2Fdoi%5C%2Fabs%5C%2F10.1139%5C%2Ff05-247%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T08%3A04%3A29Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22IPS4YIZY%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Sovacool%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222009-02%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ESovacool%20BK.%20A%20Game%20of%20Cat%20and%20Fish%3A%20How%20to%20Restore%20the%20Balance%20in%20Sustainable%20Fisheries%20Management.%20Ocean%20Development%20%26amp%3B%20International%20Law%20%5BInternet%5D.%202009%20Feb%20%5Bcited%202018%20May%2031%5D%3B40%281%29%3A97%26%23x2013%3B125.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F00908320802631486%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F00908320802631486%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22A%20Game%20of%20Cat%20and%20Fish%3A%20How%20to%20Restore%20the%20Balance%20in%20Sustainable%20Fisheries%20Management%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Benjamin%20K.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Sovacool%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22This%20article%20argues%20that%20continued%20reliance%20on%20input%5C%2Foutput%20controls%20and%20restrictions%20in%20fisheries%20management%20may%20be%20insufficient%20to%20protect%20global%20fish%20stocks.%20Instead%2C%20a%20transition%20beyond%20supply-side%20measures%20to%20those%20aimed%20at%20reducing%20demand%20for%20fish%20stocks%20may%20be%20necessary.%20The%20article%20offers%20a%20proposal%20for%20five%20types%20of%20demand-side%20or%20market-based%20measures%3A%20elimination%20of%20fishing%20subsidies%2C%20bolstering%20of%20import%20restrictions%2C%20ceasing%20trade%20in%20endangered%20and%20threatened%20fish%20stocks%2C%20strengthening%20civil%20and%20criminal%20penalties%20against%20illegal%20fishers%2C%20and%20pursuit%20of%20punitive%20trade%20sanctions%20against%20flag%20states%20flouting%20international%20fishery%20guidelines%20to%20help%20prevent%20and%20deter%20global%20overfishing.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22February%202009%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1080%5C%2F00908320802631486%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220090-8320%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F00908320802631486%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T08%3A04%3A29Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22KPYPABNG%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Leal%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222005%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ELeal%20D.%20Evolving%20Property%20Rights%20in%20Marine%20Fisheries.%20Rowman%20%26amp%3B%20Littlefield%3B%202005.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Evolving%20Property%20Rights%20in%20Marine%20Fisheries%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Donald%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Leal%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22This%20book%20examines%20the%20development%20of%20property%20rights%20in%20marine%20fisheries%2C%20and%20asks%20whether%20the%20obstacles%20to%20their%20continued%20development%20cannot%20be%20more%20easily%20overcome.%20The%20contributed%20chapters%20generally%20focus%20on%20the%20consequences%20of%20a%20lack%20of%20property%20rights%20of%20commercial%20and%20small-time%20fishers%20globally.%20National%20governments%20have%20recognized%20that%20the%20absence%20of%20such%20rights%20coupled%20with%20the%20technological%20advances%20in%20commerical%20fishing%20have%20resulted%20in%20widespread%20economic%20and%20environmental%20problems%20%28e.g.%2C%20overfishing%2C%20bycatching%2C%20highgrading%2C%20increased%20physical%20dangers%2C%20and%20lower%20profits%29.%20The%20most%20significant%20solution%20to%20these%20problems%2C%20and%20the%20predominate%20concern%20of%20this%20book%2C%20is%20the%20institution%20of%20Individual%20Transferable%20Quotas%20%28ITQs%29%2C%20also%20known%20as%20Individual%20Fishing%20Quotas%20%28IFQs%29.%20These%20are%20national%20and%20global%20policies%2C%20public-%20and%20private-sector%20managed%20allocations%20of%20the%20amount%20of%20various%20species%20of%20fish%2C%20at%20certain%20qualities%20can%20be%20harvested%20at%20particular%20times%20by%20fishers.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222005%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-0-7425-3494-0%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T08%3A04%3A29Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%224ZI2C8LG%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2045144%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Sterner%20and%20Coria%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222013-10%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ESterner%20T%2C%20Coria%20J.%20Policy%20Instruments%20for%20Environmental%20and%20Natural%20Resource%20Management.%20Routledge%3B%202013.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Policy%20Instruments%20for%20Environmental%20and%20Natural%20Resource%20Management%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Thomas%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Sterner%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Jessica%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Coria%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Thomas%20Sterner%27s%20book%20is%20an%20attempt%20to%20encourage%20more%20widespread%20and%20careful%20use%20of%20economic%20policy%20instruments.%20The%20book%20compares%20the%20accumulated%20experiences%20of%20the%20use%20of%20economic%20policy%20instruments%20in%20the%20U.S.%20and%20Europe%2C%20as%20well%20as%20in%20rich%20and%20poor%20countries%20in%20Asia%2C%20Africa%2C%20and%20Latin%20America.%20Ambitious%20in%20scope%2C%20it%20discusses%20the%20design%20of%20instruments%20that%20can%20be%20employed%20in%20any%20country%20in%20a%20wide%20range%20of%20contexts%2C%20including%20transportation%2C%20industrial%20pollution%2C%20water%20pricing%2C%20waste%2C%20fisheries%2C%20forests%2C%20and%20agriculture.%20While%20deeply%20rooted%20in%20economics%2C%20Policy%20Instruments%20for%20Environmental%20and%20Natural%20Resource%20Management%20is%20informed%20by%20political%2C%20legal%2C%20ecological%2C%20and%20psychological%20research.%20The%20new%20edition%20enhances%20what%20has%20already%20been%20widely%20hailed%20as%20a%20highly%20innovative%20work.%20The%20book%20includes%20greatly%20expanded%20coverage%20of%20climate%20change%2C%20covering%20aspects%20related%20to%20policy%20design%2C%20international%20equity%20and%20discounting%2C%20voluntary%20carbon%20markets%2C%20permit%20trading%20in%20United%20States%2C%20and%20the%20Clean%20Development%20Mechanism.%20Focusing%20ever%20more%20on%20leading%20ideas%20in%20both%20theory%20and%20policy%2C%20the%20new%20edition%20brings%20experimental%20economics%20into%20the%20main%20of%20its%20discussions.%20It%20features%20expanded%20coverage%20of%20the%20monitoring%20and%20enforcement%20of%20environmental%20policy%2C%20technological%20change%2C%20the%20choice%20of%20policy%20instruments%20under%20imperfect%20competition%2C%20and%20subjects%20such%20as%20corporate%20social%20responsibility%2C%20bio-fuels%2C%20payments%20for%20ecosystem%20services%2C%20and%20REDD.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22October%202013%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-1-317-70387-7%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22HV6G547Y%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-01T08%3A04%3A28Z%22%7D%7D%5D%7D

1.

FAO. Contributing to food security and nutrition for all. Rome; 2016. (The state of world fisheries and aquaculture).

1.

Daly HE, Farley J. Ecological Economics, Second Edition: Principles and Applications. Island Press; 2011.

1.

Costanza R, Cumberland JH, Daly H, Goodland R, Norgaard RB, Kubiszewski I, et al. An Introduction to Ecological Economics, Second Edition. CRC Press; 2014.

1.

Ostrom E. The Challenge of Common-Pool Resources. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development [Internet]. 2008 Jul [cited 2018 May 31];50(4):8–21. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.3200/ENVT.50.4.8-21

1.

Grafton RQ, Arnason R, Bjørndal T, Campbell D, Campbell HF, Clark CW, et al. Incentive-based approaches to sustainable fisheries. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences [Internet]. 2006 Mar [cited 2018 May 31];63(3):699–710. Available from:

http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/abs/10.1139/f05-247

1.

Sovacool BK. A Game of Cat and Fish: How to Restore the Balance in Sustainable Fisheries Management. Ocean Development & International Law [Internet]. 2009 Feb [cited 2018 May 31];40(1):97–125. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1080/00908320802631486

1.

Leal D. Evolving Property Rights in Marine Fisheries. Rowman & Littlefield; 2005.

1.

Sterner T, Coria J. Policy Instruments for Environmental and Natural Resource Management. Routledge; 2013.