“So they knew” – How Unfair Distribution has fuelled the Climate Crisis

Written by Alice Booth

“They dumped millions of dollars into lobbying a campaign of doubt”, announced Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in September, highlighting the decades long effort by the oil and gas industry to spread disinformation and denial over the very existence of climate change [1-2]. This announcement comes amid a Supreme Court legal dispute and fraud investigation of ExxonMobil, after it was revealed that the company was fully aware of the dangers of climate change as early as 1977 with one internal report by Exxon scientist James Black noting that “a doubling of carbon dioxide is estimated to be capable of increasing the average global temperature by 1-3°C” [3].

In what can only be termed pure self-interest, Exxon and significant stakeholders such as the billionaire Koch Brothers, used their extreme financial clout to invest substantial time and money into climate denial campaigns to manufacture the so-called ‘climate debate’ and deliberately slow society’s response to climate change [4]. By the 1990s the campaign had mutated into a sprawling network of PR firms, industry execs, and pro-oil thinktanks who used the media’s eagerness to appear impartial to position industry funded deniers-with-doctorates as experts of opposite and equal importance to legitimate climate scientists, rather than simply biased and anomalous outliers [5]. And it worked. In 2010 American belief in climate change hit just 48% - how can we tackle climate change when voters don’t even believe in it [5]?

This is not a new phenomenon. In 1964, US Surgeon General Luther Terry successfully highlighted the role of cigarettes in causing lung cancer [6]. Out of fear for their profits, the tobacco industry proceeded to cloud the conversation with disinformation for decades, diverting funding away from innovative cancer research that could’ve saved millions of lives. And now the public is being bamboozled again when the stakes could not be higher.

So how do they do it? The answer is simple and depressingly obvious – money. The fossil fuel industry is one of the most lucrative sectors of the world economy and those lucky few have made their fortune in it. They aren’t slowing down either – since the 2015 Paris Agreement, the five largest public oil & gas companies have invested over $1 billion into the climate-denial machine [7]. This is not okay. If extreme wealth can change the course of social and scientific progress, just to earn a few bucks, then how can we possibly say that we live in a fair and equal democracy?

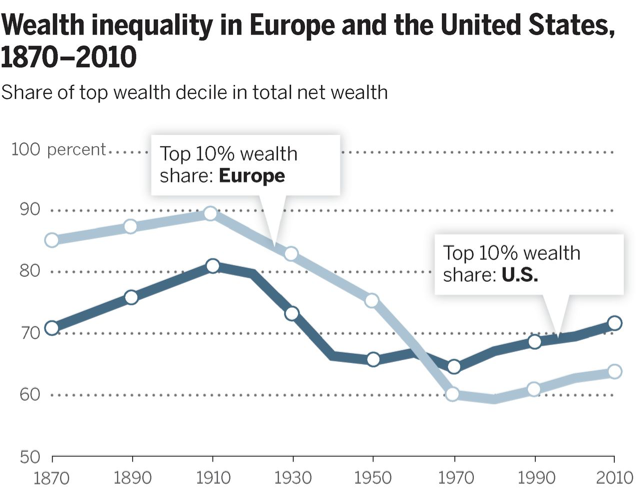

Wealth and political influence go hand in hand and in 2017, the richest 1% was found to own over half of the world’s total wealth [8]. This unfair distribution of wealth is a direct driver of the climate crisis we find ourselves in. As Thomas Piketty notes in his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the issue is wealth inequality rather than income [9]. Wealth refers to the assets you possess whereas income is the money you earn from these assets [10]. The more wealth you have, the more sources of income you have which ultimately increases your wealth, feeding a self-fulfilling spiral that widens the gap between the rich and poor. Moreover, in a period of low economic growth, such as today, the rate of return to capital, r, (interest rates) is greater than the growth rate, g, (increase in wages) so wealth grows at a faster rate than income (r>g) and wealth inequality increases [9,11]. In the mid-20th century, wealth inequality dramatically decreased, reflecting the destruction of assets through war and social unrest (see fig. 1), but since the 1970s wealth inequality has been on the rise again, reflecting the declining growth rate [11].

Fig. 1: Wealth inequality in Europe and the US from 1870-2010. The share of net wealth in the hands of the top 10% dropped significantly in the mid-20th century but has been rising steadily since [11]

So, what can be done? Piketty suggests that a series of progressive wealth taxes are required to limit extreme wealth whilst encouraging economic growth to boost income and reduce the gap between the Haves and Have-nots [9]. Daly and Farley, meanwhile, propose several solutions including caps on income and wealth, negative income taxes, or land taxes which would directly target the sources of wealth [12]. But unfair distribution is by no means the only driver of the climate crisis and by focusing efforts on boosting growth we may only make the situation worse by pushing consumption beyond the sustainable scale of Earth’s planetary boundaries [13-14].

The solution isn’t clear, but it is clear that human capacity to successfully tackle climate change has been irretrievably damaged by the self-serving actions of a few wealthy oil tycoons. And we should not let them get away with it.

References

[1] Holden, E., 2019. Exxon sowed doubt about climate crisis, House democrats hear in testimony. The Guardian, 23 October.

[2] Frazin, R., 2019. Ocasio-Cortez: Exxon Mobil knew exactly what it was doing. The Hill, 11 November.

[3] Black, J., 1977. Summary of a presentation on the CO2 greenhouse effect that Black gave to top Exxon executives and other company scientists.

[4] McKibben, B., 2015. What Exxon knew about climate change. The New Yorker, 18 September.

[5] Westervelt, A., 2019. How the fossil fuel industry got the media to think climate change was debatable. The Washington Post, 10 January.

[6] The Climate Reality Project, 2019. The Climate Denial Machine: How the fossil fuel industry blocks climate action. The Climate Reality Project, 5 September.

[7] Influence Map, 2019. Big Oil's Real Agenda on Climate Change.: An InfluenceMap Report.

[8] Credit Suisse Research Institute , 2017. Global Wealth Report 2017, Zurich: Credit Suisse.

[9] Piketty, T., 2014. Capital in the Twenty-Firsy Century. (Translated by Arthur Goldhammer). 1st ed: Harvard University Press.

[10] Daly, H. E. & Farley, J., 2011. Chapter 16: Distribution. In: Ecological Economics: Principles and Applications. 2nd ed. Washington: Island Press, pp. 301-320.

[11] Piketty, T. & Saez, E., 2014. Inequality in the long run. Science, 344(6186), pp. 838-843.

[12] Daly, H. E. & Farley, J., 2011. Chapter 23: Just Distribution. In: Ecological Economics: Principles and Applications. 2nd ed. Washington: Island Press, pp. 441-456.

[13] Steffen, W. et al., 2015. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347(6223), p. 736.

[14] Daly, H. & Farley, J., 2011. Chapter 22: Sustainable Scale. In: Ecological Economics: Principles and Applications. 2nd ed. Washington: Island Press, pp. 428-440.